CUDA introduction

Initially developed for 3D rendering in video games, GPU devices probably contributed to a great extent to the cambrian explosion of machine learning, and in particular deep learning because of their great abilities at parallelism. Indeed, at its heart, deep learning is not much more than a lot of operations on elements of vector spaces, such as matrix and vector multiplications in the compositions of layers, as well as scalar operations like in activations functions. Most of those operations can be decomposed in multiple independent computations that can be then evaluated concurrently.

By providing huge increases in throughput on those kind of operations, GPU are naturally pieces of hardware that allow to greatly reduce training time of large deep learning models and are today ubiquitous in any modern and large scale machine learning pipeline.

The rest of this post focuses on Nvidia GPU and its CUDA SDK, so the architecture points mentioned can varies for other manufacturers

GPU architecture

To understand how CUDA works and how to program CUDA kernels, it is absolutely necessary to have a basic understanding about the hardware architecture of Nvidia GPU.

Differences with CPU

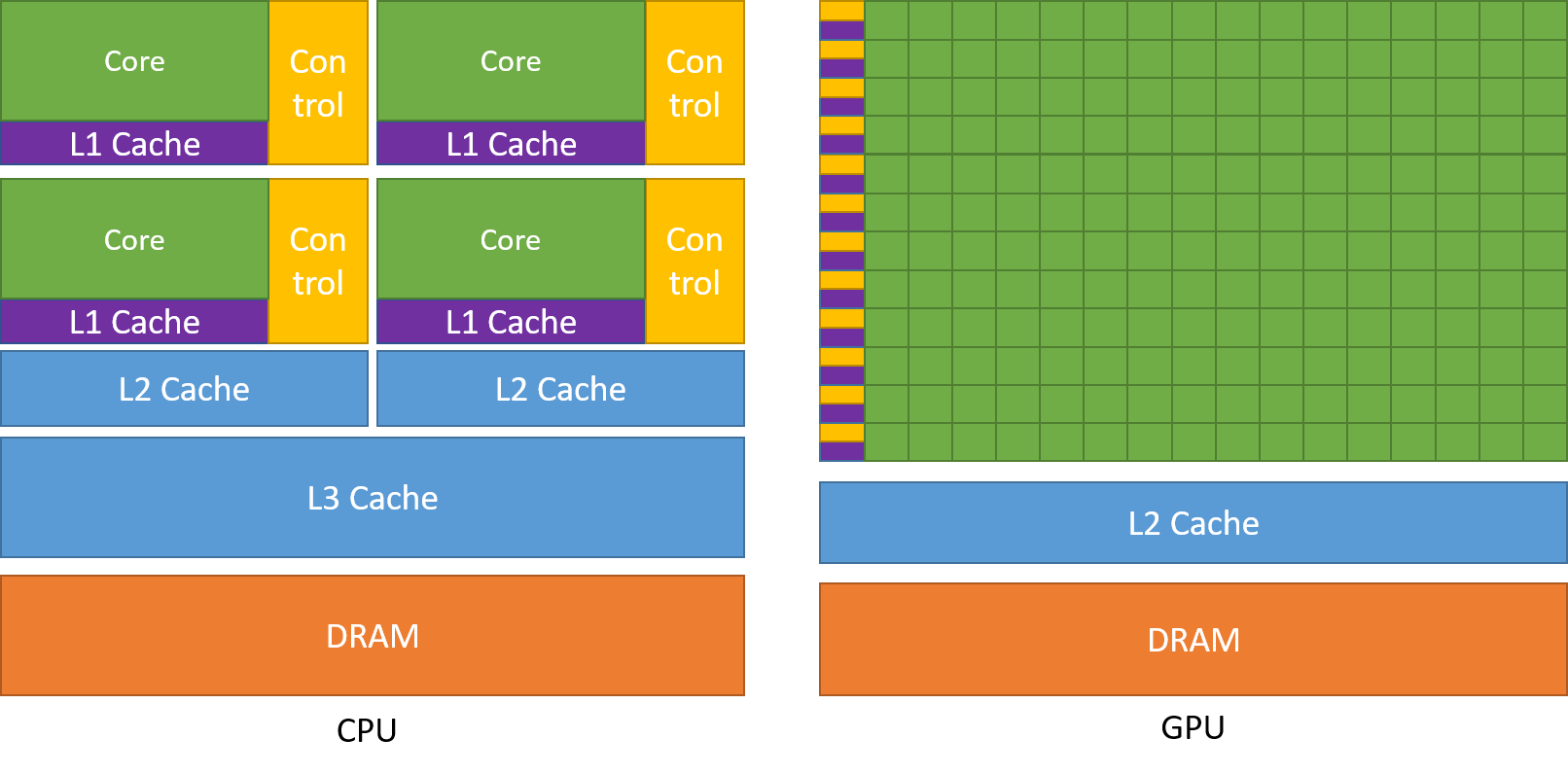

CPU are compute units that excel at sequential tasks, they are designed to reduce latency through their relative low amount of cores (and by extension the limited number of threads they can handle concurrently) and their caches used to hide latency.

On the other hand, GPU are characterized by their very large number of cores that can run threads concurrently in the whole unit. They are indeed specifically designed for parallelism and try to optimize throughput instead of directly minimizing latency like CPU do.

Compute hierarchy

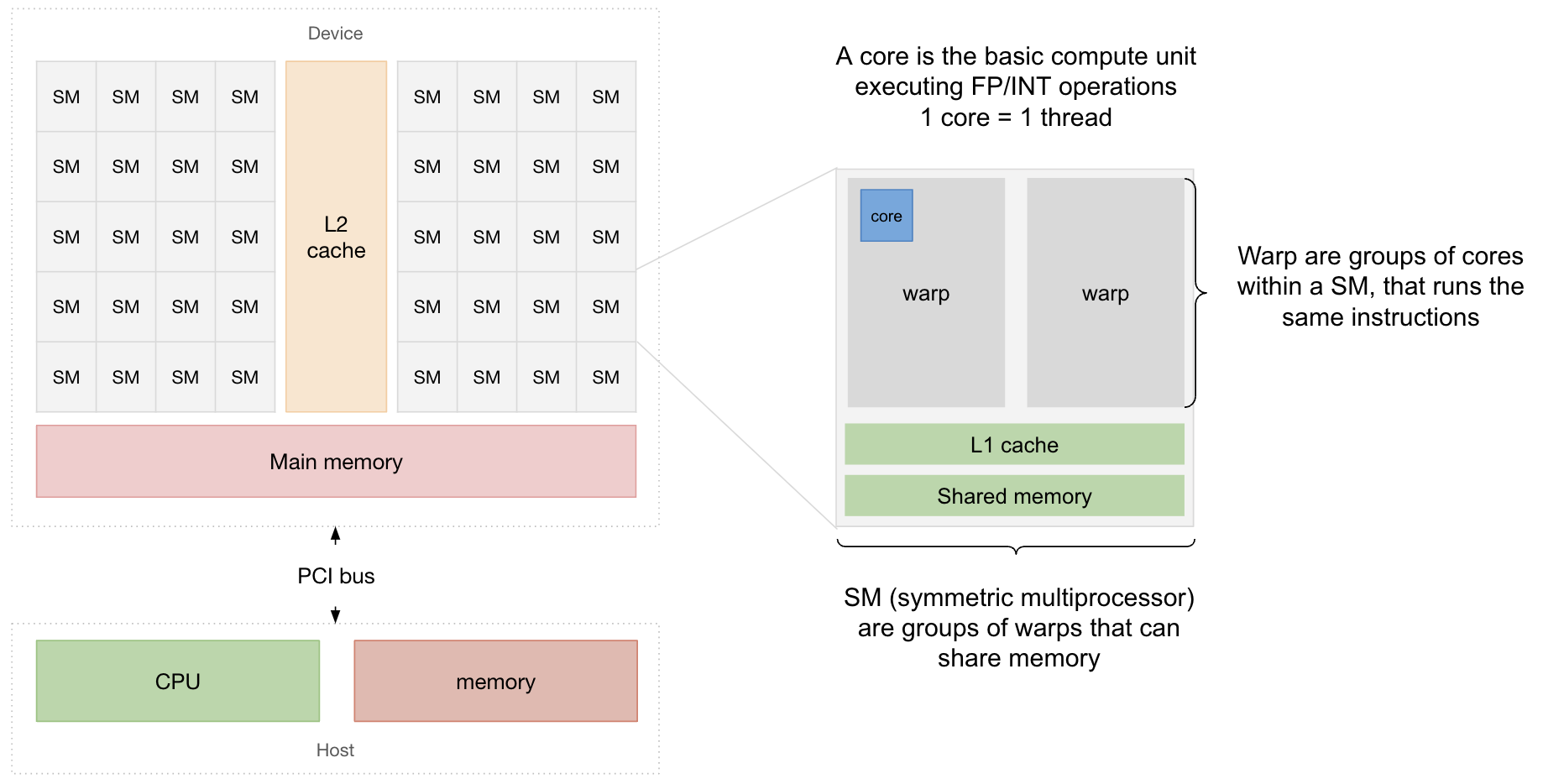

Within a GPU, compute units are organized hierarchically:

- the most basic compute unit is a core. It is it that executes all the floating point or integer operations defined in the program.

- cores are grouped into processing blocks (such as “32-core processing blocks” in Nvidia GPU) and those processing blocks are the basic units running the CUDA kernel. Threads of cores within processing blocks will run the same instruction.

- processing blocks are grouped into symmetric multi-processors (SM) where blocks within the same SM can have their threads share data and also be synchronized.

Memory hierarchy

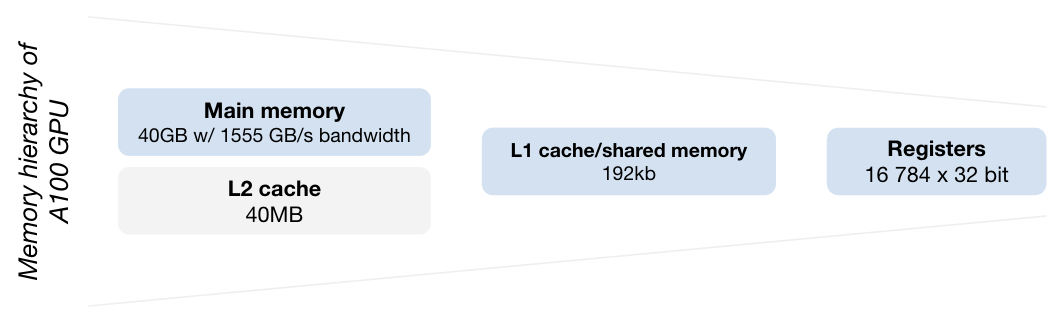

Following the compute hierarchy, a GPU have different memory units at each level:

- Registers are small but very fast memory within a SM, that are shared equally by the processing blocks of the SM. Variables stored in register memory are private to each thread and thus exists only for the lifetime of the thread.

- Local memory is private to each thread and is used to store variables that cannot fit within registers, it also persists data for the lifetime of the thread. It has the same latency as the global memory and as such is slower than register’s access latency.

- Shared memory are blocks of memory at SM level that can be accessed by every thread in blocks of the same SM, allowing local threads to communicate with each others. Variables stored in this shared space must be declared prefixed with the

__shared__keyword. This memory is very fast. - Global memory is the biggest memory space on the GPU but also the slower. All the data stored there is accessible by every thread in every block of every SM and persists until manually freed. This means that multiple kernel can reuse data stored in the global memory to avoid the costly transfers from CPU RAM and the GPU.

CUDA concepts

CUDA provides a bunch of methods and keywords to C and C++, giving a flexible way to move data from the CPU (called host) to the GPU (called device) and run instructions directly on it.

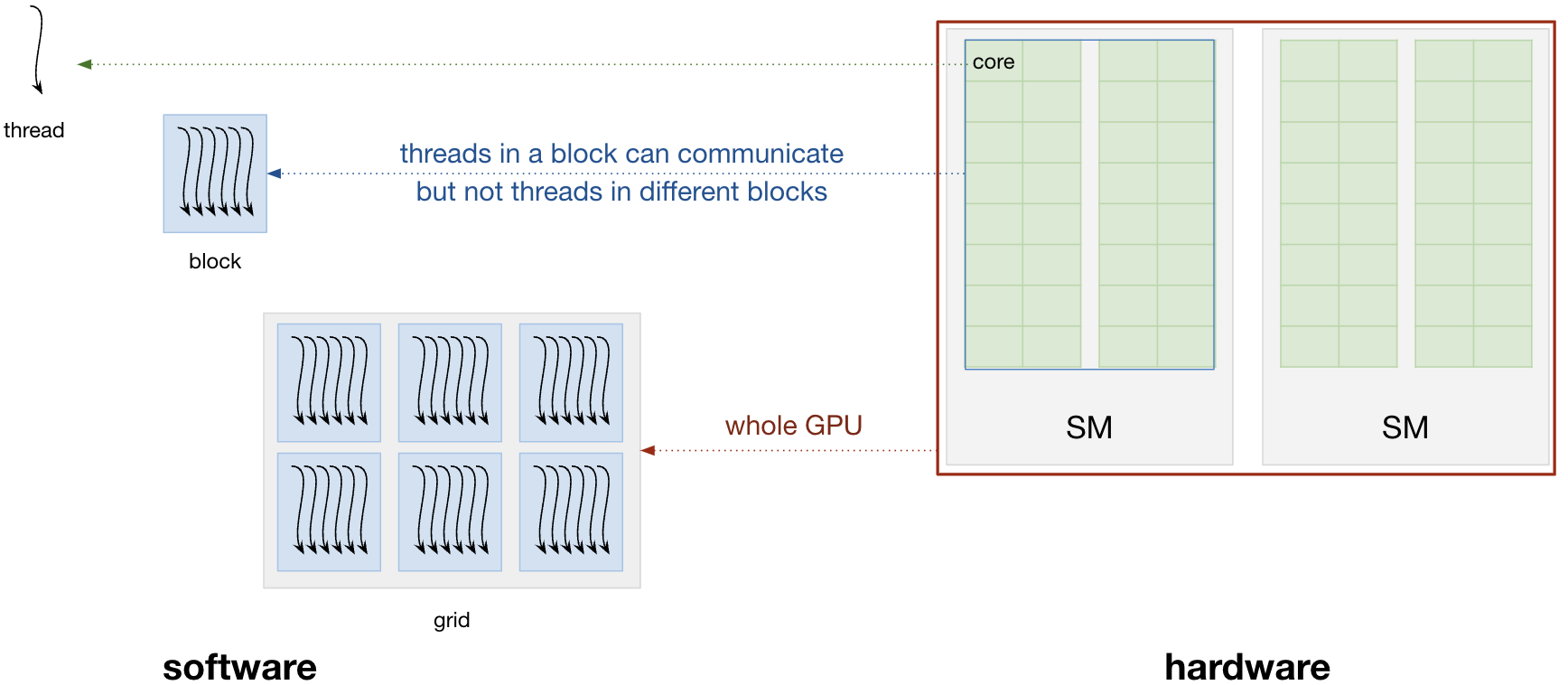

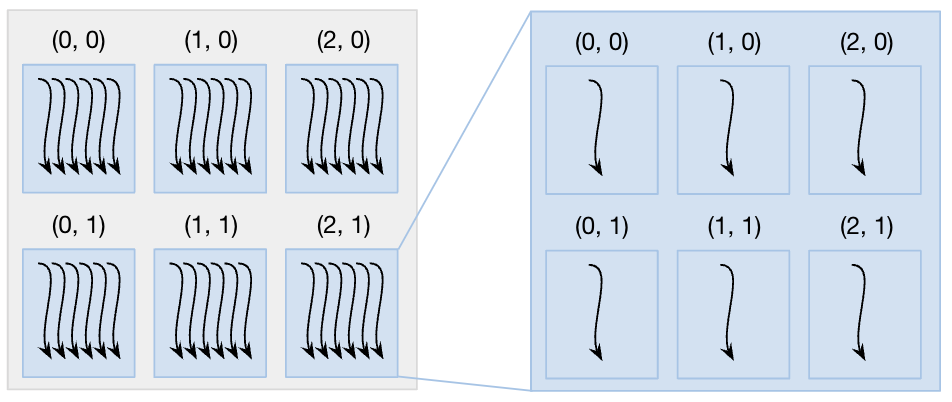

The concepts used to declare and run kernels are nicely symmetrical to the hardware of Nvidia GPU:

- a thread executes the kernel such that different threads can run the same kernel independently and concurrently. A thread is a 1-to-1 mapping to a core.

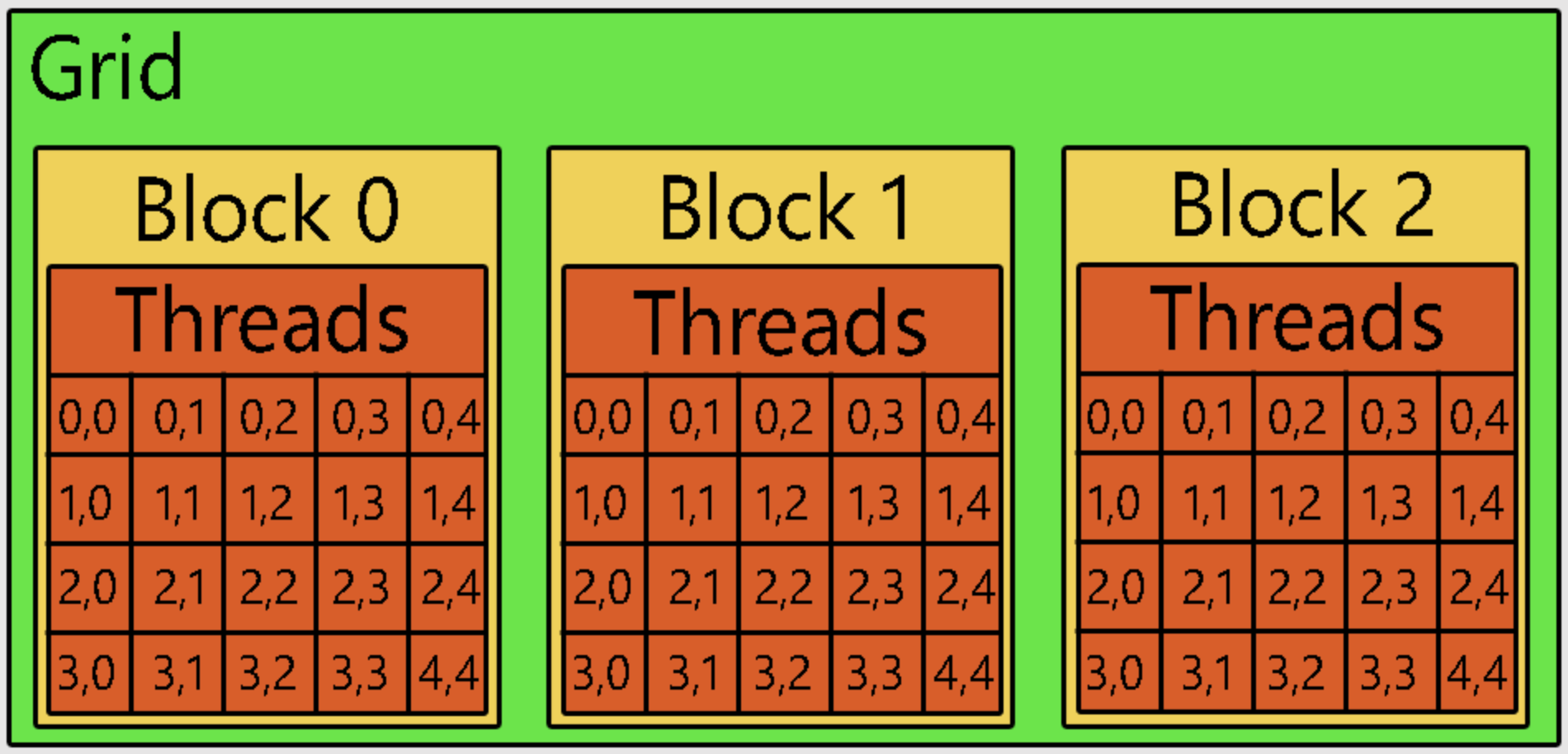

- threads are arranged together in blocks and run on the same SM, hence the size of the thread block has to be a multiple of the warp size and up to the hardware limit. Threads within a block can share data and be synchronized if necessary, which is not possible for threads of different blocks.

- blocks are organized in the grid which can be seen as the whole GPU. Within it, blocks are executed independently and with no particular order: it is the job of the run-time to dispatch the blocks such that the GPU is used efficiently (and there is no guarantee about order).

Kernel invocation

Kernels are invoked on the host just like regular C functions, but with an additional syntactical element to pass the launch configuration:

1

myKernel<<<gridSize, blockSize>>>(...)

where gridSize and blockSize indicates the number of blocks in the grid (and their arrangement structure) and the number of threads per blocks respectively. Those two arguments can either be integers for 1d arrangements, or of the type dim3 which is a special data structure from CUDA. dim3 variables are 1d, 2d or 3d vectors:

| declaration | description |

|---|---|

dim3 blockSize(256) | 256 threads along the x axis |

dim3 blockSize(4, 64) | 256 threads with 4 rows of 64 threads along the y axis |

dim3 blockSize(2, 2, 64) | 256 threads with two rows of 2 columns of 64 threads along the z axis |

Thread indexing

While the block size - the number of threads within a block - is set to be a multiple to the warp size, it can be structured either in a 1d, 2d or 3d arrangement depending of the problem to solve. For instance, if we only do vector operations, we might want to stick to the simple 1d arrangement to index our threads in each blocks, while of we process images, a 2d arrangement will make things easier.

Similarly, the arrangement of blocks in a grid can also be 1d, 2d or 3d depending on the problem we are interested in solving.

Those two structures are the basis of the kernel launch configuration provided when we invoke the kernel on the host, and that is used by the run-time to organize and dispatch the kernel on the device.

Because kernels are executed identically and concurrently on threads, we need a way to know what slices of data a particular thread has to process to avoid any overlaps. Hopefully, CUDA provides a set of built-in data structures and variables allowing to uniquely identify a thread in a block and in a grid:

| variable | type | signification |

|---|---|---|

threadIdx | dim3 | unique thread identifier within its block. It can have up to 3 dimensions depending on the block structure. |

blockIdx | dim3 | unique block identifier within the grid. It can also have up to 3 dimensions. |

blockDim | dim3 | vector with 3 components where each component stores the number of threads along the axis e.g. for a 1d block arrangement of 32 threads, blockDim.x = 32 |

gridDim | dim3 | Number of blocks in the grid along an axis, similarly to blockDim |

warpSize | int | Number of threads in a warp |

From those variables, we can build an unique global id of a thread within a kernel. For instance, for a 1d block arrangement of threads in a 1d grid:

1

id = blockDim.x * blockIdx.x + threadIdx.x

Similarly, the get the global thread index in a 1d grid of 2d blocks, we have to first traverse all the previous blocks (blockDim.x * blockDim.y * blockIdx.x), then the rows of the thread block (blockDim.x * threadIdx.y):

1

id = blockDim.x * blockDim.y * blockIdx.x + blockDim.x * threadIdx.y + threadIdx.x

Functions invocation and execution location

Because we have 2 places where methods can be called and instructions executed, the compiler needs a way to know where to compile to. CUDA introduces 3 keywords for that.

The __global___ keyword indicates to the compilers that while the method runs on the GPU, it will be invoked from the host. Kernels falls into this, so you need to prefix your kernel declaration with this keyword:

1

2

3

__global__ void myKernel(...) {

// do stuff

}

While declaring kernels, you might find yourself in need for helper methods to re-use across kernels (for instance mathematical functions). You can declare them as function living entirely in the GPU: both invoked and executed on the device, using the keyword __device__ prefixing the function declaration:

1

2

3

__device__ void myMathFunction(...) {

// do stuff

}

Finally, CUDA also provides the __host__ keyword, indicating to the compiler that the method will both be invoked and executed on the host. Nevertheless, this is the default when writing C code, so I’m not sure if this keyword is really used in practice (perhaps some edge cases?).

Memory management

Just like regular in C, you have to manually manage the memory with CUDA objects as well. Hopefully, CUDA provides useful built-in methods that mimic C ones to do that:

cudaMalloc(void **ptr, size_t size)allocatessizeof memory on the device and pointsptrto the allocated memory address on the device.cudaMemcpy(void *dest, void *source, size_t size, cudaMemcpyKind direction)copy the data fromsourcetodesteither from the host to the device (direction = cudaMemcpyHostToDevice) or from the device to the host (direction = cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost).cudaFree(void *ptr)to free the allocated memory on the device.

In a classic program invoking a CUDA kernel, we basically always find this overall pattern

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

int main(void) {

// do stuff on the CPU...

// declare device pointers

float *d_x, *d_out;

// allocate on the device

cudaMalloc((void**)&d_x, sizeof(float));

cudaMalloc((void**)&d_out, sizeof(float));

// copy data to the device

cudaMemcpy(d_x, h_x, sizeof(float), cudaMemcpyHostToDevice);

// define the launch configuration

dim3 blockSize(...);

dim3 gridSize(...);

// invoke kernel

myKernel<<<gridSize, blockSize>>>(h_x, d_out);

// get results

cudaMemcpy(h_out, d_out, sizeof(float), cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost);

// free device memory

cudaFree(h_x); cudaFree(h_out);

// do stuff on the CPU...

}

Kernel example

Let’s add two vectors on GPU to harness parallelism. Here is a sample piece of code applying the pattern see above, but applied to vector addition:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

int main(void) {

// do stuff with the CPU

int h_n = 1000000;

float *h_x, *h_y, *h_c, *d_x, *d_y, *d_c;

// fill h_x and h_y with some data, h_c stays empty

...

// allocate memory on the GPU

cudaMalloc( (void**)&d_x, h_n*sizeof(float) );

cudaMalloc( (void**)&d_y, h_n*sizeof(float) );

cudaMalloc( (void**)&d_c, h_n*sizeof(float) );

// transfer data from CPU to the GPU

cudaMemcpy( d_x, h_x, h_n*sizeof(float), cudaMemcpyHostToDevice );

cudaMemcpy( d_y, h_y, h_n*sizeof(float), cudaMemcpyHostToDevice );

cudaMemcpy( d_c, h_c, h_n*sizeof(float), cudaMemcpyHostToDevice );

// define kernel dispatch config

dim3 block_size(256);

dim3 grid_size( (h_n + block_size.x - 1) / block_size.x );

// launch the kernel

vectorAdd<<< grid_size, block_size >>>(d_x, d_y, d_c, h_n);

// transfer results back to the CPU

cudaMemcpy( h_c, d_c, h_n*sizeof(float), cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost );

// free device memory

cudaFree(d_x); cudaFree(d_y); cudaFree(d_c);

// do stuff with the CPU

}

The CUDA kernel is very, very simple:

1

2

3

4

5

6

__global__ void vectorAdd(float *x, float *y, float *c, int n) {

int i = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (i < n)

c[i] = x[i] + y[i];

}